Transplant Immunosuppression: How Tacrolimus, Mycophenolate, and Steroids Work Together After Kidney Transplant

Dec, 24 2025

Dec, 24 2025

After a kidney transplant, your new organ is under constant threat-not from infection or injury, but from your own immune system. It doesn’t know the difference between a donated kidney and a virus. That’s where tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and steroids come in. Together, they form the backbone of modern kidney transplant care. This isn’t just a list of pills. It’s a carefully balanced system designed to keep your transplant alive while keeping you safe from serious side effects.

Why You Need All Three Drugs

For decades, transplant teams tried to stop rejection with one or two drugs. It didn’t work well enough. Cyclosporine, once the go-to, still led to rejection in more than 20% of patients. Then, in the mid-1990s, doctors started combining tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and steroids-and everything changed. Acute rejection rates dropped from 21% to just 8.2%. That’s a 60% improvement. This triple combo became the new standard, and it’s still used in about 70% of new kidney transplants today.Each drug plays a different role. Tacrolimus stops T-cells from attacking the new kidney. Mycophenolate blocks the growth of B-cells and other immune cells that help the body recognize the transplant as foreign. Steroids hit the brakes on inflammation across the whole system. Alone, each drug has limits. Together, they cover more ground and let doctors use lower doses of each-reducing side effects without losing protection.

Tacrolimus: The Precision Tool

Tacrolimus, also known as FK506, is a calcineurin inhibitor. It works fast-within 12 to 24 hours-and peaks in your blood within 1.5 to 3 hours after you take it. But here’s the catch: it’s not forgiving. Too little, and your kidney gets rejected. Too much, and you risk kidney damage, nerve problems, or even diabetes. That’s why doctors monitor your blood levels closely.In the first year after transplant, your target level is usually between 5 and 10 ng/mL. But it’s not just about the number at one point in time. New research shows that measuring the total drug exposure over 12 hours-called the AUC-is more accurate than just checking your trough level. Some centers are already switching to this method. Doses are adjusted weekly at first, then every few months. You’ll need regular blood tests, and you can’t skip them.

Common side effects include shaky hands, headaches, and high blood pressure. About 1 in 5 people develop post-transplant diabetes. That’s why many patients are put on a low-sugar diet and checked for blood sugar spikes every few months. It’s not just about the transplant anymore-it’s about managing a new chronic condition.

Mycophenolate: The Growth Blocker

Mycophenolate (often sold as MMF or CellCept) is a prodrug. Your body turns it into mycophenolic acid, which shuts down the production of DNA in immune cells. No DNA, no new immune cells. No new immune cells, less chance of rejection.Standard dose? 1 gram twice a day. But here’s the reality: 20 to 30% of people can’t stick with that dose. Why? Stomach problems. Diarrhea, nausea, vomiting-these are common. Some patients lose weight, feel exhausted, or can’t work because they’re stuck near a bathroom. If symptoms don’t improve, doctors reduce the dose to 500 mg twice daily. If that still doesn’t help, they may switch to mycophenolate sodium (Myfortic), which is easier on the gut.

Another big issue? Low white blood cell count. About 15% of patients develop leukopenia. That doesn’t mean you’re sick-it means your immune system is too suppressed. Your doctor will check your CBC every week at first. If your white count drops too low, they’ll pause the drug or lower the dose. It’s a balancing act: protect the kidney, but don’t leave you defenseless against infections.

Steroids: The Quick Fix with a Long-Term Cost

Steroids-usually methylprednisolone or prednisone-are the oldest weapons in the transplant arsenal. You get a big 1,000 mg IV dose right in the operating room. Then, over the next few weeks, the dose drops like a stone: down to 15 mg a day by 3 to 4 weeks, then 10 mg by 2 to 3 months.Why taper so fast? Because steroids are powerful, but they’re also dangerous over time. Weight gain, acne, moon face, stretch marks, mood swings, trouble sleeping, bone thinning, high cholesterol-they all add up. For many patients, these side effects are worse than the transplant itself. That’s why doctors now ask: Do we even need them?

Studies from 2005 showed that patients who skipped steroids entirely-using tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and an induction drug called daclizumab-had the same rejection rates as those on the full steroid combo. About 89% of those patients stayed steroid-free after six months. Today, steroid-free protocols are growing. They’re not for everyone, but if you’re young, healthy, and at low risk for rejection, your team might offer it.

What Goes Wrong-and How It’s Fixed

Even with perfect dosing, things can go sideways. One of the biggest problems is drug interactions. If you’re on a proton pump inhibitor like omeprazole for heartburn, it can block your body from absorbing mycophenolate. That means less drug in your blood, higher rejection risk. Always tell your pharmacist and transplant team about every pill, supplement, or herbal remedy you take.Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is another sneaky threat. It’s a common virus that stays quiet in most people. But after a transplant, your immune system is too weak to keep it in check. CMV can cause fever, fatigue, and even damage the new kidney. You’ll get tested regularly and often take antiviral pills like valganciclovir for the first 3 to 6 months.

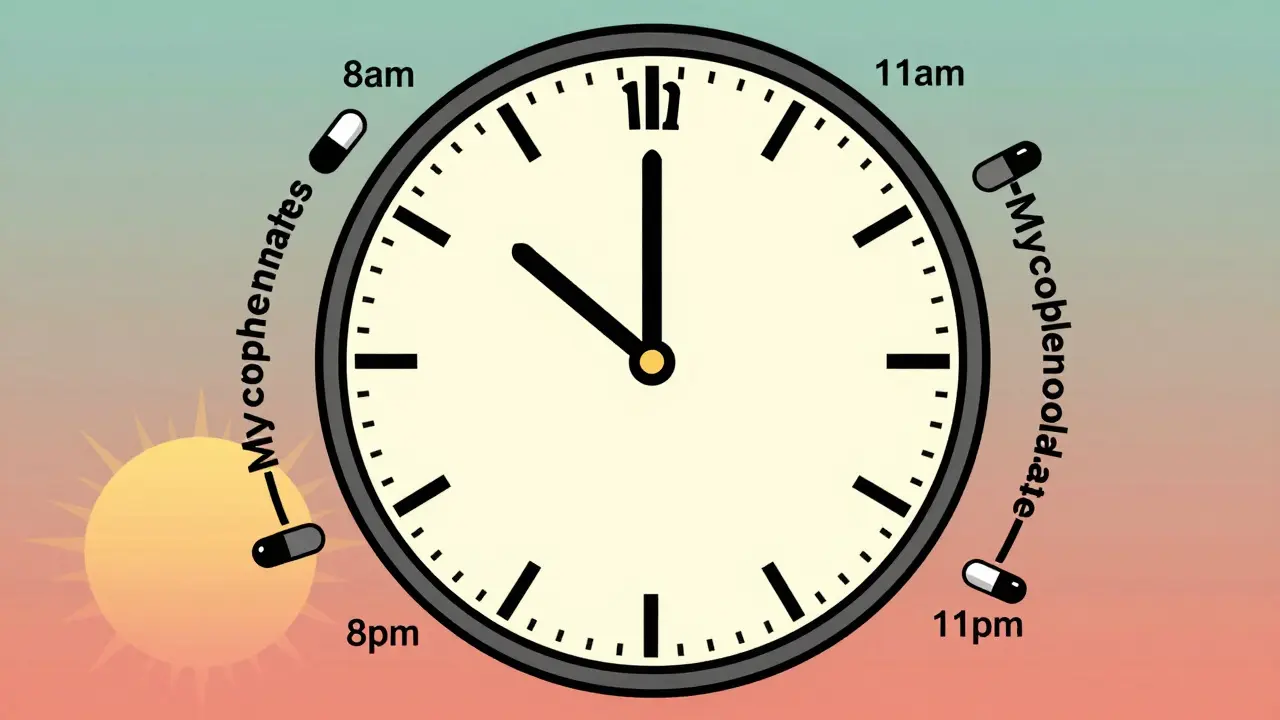

Another issue? Timing. Tacrolimus and mycophenolate should be taken 2 to 4 hours apart. If you take them together, your stomach can’t absorb them properly. Many patients set phone alarms: one at 8 a.m., the other at 11 a.m., then again at 8 p.m. and 11 p.m. It’s a grind-but it’s the difference between keeping your kidney and losing it.

The Big Picture: Success and Limits

This triple therapy works incredibly well in the first year. Most people feel great. Their energy comes back. They return to work. They travel. But here’s the hard truth: 25% of adult kidney transplant recipients still lose their graft within five years. Why? Because these drugs don’t stop chronic injury. Over time, even with perfect levels, the kidney slowly scars. Blood vessels narrow. Tissue stiffens. It’s not rejection-it’s something slower, harder to detect, and harder to treat.That’s why researchers are pushing for personalized medicine. Some labs now test your genes to see how fast you metabolize tacrolimus. Others are looking at blood markers that predict rejection before it happens. In the next five years, we’ll see fewer people on fixed doses and more on tailored plans based on your body’s unique response.

Right now, the goal is simple: keep the kidney alive, keep you healthy, and keep side effects under control. It’s not perfect. But for millions of people around the world, this three-drug combo is the reason they’re alive today.

What Comes Next?

The future of transplant immunosuppression isn’t about adding more drugs. It’s about removing the ones that hurt more than they help. Steroid-free protocols are expanding. New drugs like belatacept are being tested to replace calcineurin inhibitors entirely. And AUC monitoring is becoming standard, not experimental.But until those alternatives are proven for everyone, the triple combo remains the most reliable tool we have. If you’re on it, don’t skip your blood tests. Don’t ignore the side effects. Talk to your team. There’s a reason they ask you the same questions every visit. It’s not bureaucracy-it’s survival.

Can I stop taking my immunosuppressants if I feel fine?

No. Even if you feel great, stopping your meds-even for a day-can trigger rejection. The immune system doesn’t wait for symptoms. It reacts silently. Many patients lose their transplant because they skipped doses during travel, illness, or because they thought they were "off the hook." There’s no safe time to stop. Lifelong adherence is the rule.

Why do I need blood tests so often?

Tacrolimus has a very narrow range between too little and too much. A level of 4 ng/mL might mean rejection risk. A level of 12 ng/mL could cause nerve damage or kidney toxicity. Your body’s ability to absorb and break down the drug changes with diet, other medications, infections, and even stress. Weekly tests early on help your team fine-tune your dose. After a year, you may only need tests every 1-3 months, but never skip them.

Is mycophenolate the same as CellCept?

Yes. CellCept is the brand name for mycophenolate mofetil (MMF). There’s also a generic version and a different form called mycophenolate sodium (Myfortic), which is absorbed differently and may cause fewer stomach issues. Your doctor will choose based on your tolerance and cost. Don’t switch brands without checking with your transplant team-they’re not interchangeable without monitoring.

Can I drink alcohol while on these drugs?

Moderation is key. Alcohol can worsen liver damage from tacrolimus and raise blood pressure. It can also interact with steroids, increasing the risk of stomach ulcers. Most transplant teams allow one drink a day for women and two for men-but only if your liver and blood pressure are stable. Always check with your doctor first. Some patients are told to avoid it completely, especially if they have diabetes or fatty liver disease.

Do these drugs increase cancer risk?

Yes. All immunosuppressants lower your body’s ability to detect and destroy abnormal cells. Skin cancer is the most common-up to 10 times higher risk than the general population. That’s why annual full-body skin checks are mandatory. Other risks include lymphoma and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD), especially in younger patients. Protect your skin, avoid tanning beds, wear hats, and report any new moles or sores that don’t heal.

Final Thoughts

This isn’t just about taking pills. It’s about adapting to a new normal. You’ll learn to read your body. You’ll learn to question every new medicine, every supplement, every cold you catch. You’ll learn that your transplant isn’t a cure-it’s a partnership. And the drugs you take are the bridge between your old life and your new one.For now, the combination of tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and steroids is still the gold standard. It’s not perfect. But for millions, it’s the reason they’re alive to see another sunrise.

Bailey Adkison

December 26, 2025 AT 02:59Tacrolimus levels need to be monitored with surgical precision not because doctors are paranoid but because biology doesn't care about your schedule

One ng/mL off and you're playing Russian roulette with your new kidney

No excuses

Skipping blood tests is not a lifestyle choice it's medical negligence

Carlos Narvaez

December 26, 2025 AT 22:11Triple therapy is the gold standard for a reason

Any deviation is a gamble with unproven outcomes

Myth: steroid-free protocols are better

Reality: they're for low-risk outliers not the general population

Harbans Singh

December 28, 2025 AT 04:36This is such a clear breakdown thanks for sharing

I'm from India and we have a lot of transplant patients here

Many don't understand why they need all three meds

It's not just about the science it's about making people feel seen in their struggle

Hope this helps someone reading this late at night feeling overwhelmed

Justin James

December 28, 2025 AT 19:17Let me tell you something they don't want you to know

The entire transplant immunosuppression industry is built on fear and profit

Tacrolimus costs $500 a month but the active ingredient could be synthesized for $2

Why do they keep you on steroids when studies show you don't need them

Because if you stop the drugs you stop the revenue stream

CMV testing? That's a money grab too

They want you dependent forever

They'll never admit the real reason they won't go steroid-free is because it cuts into their bottom line

They're not saving lives they're selling lifelong dependency

And the blood tests

Every single one of them is a billing code

Wake up people this isn't medicine it's a corporate machine

Rick Kimberly

December 29, 2025 AT 19:59The pharmacokinetic variability of mycophenolate across different populations warrants further investigation

Especially in non-Caucasian cohorts where metabolic enzyme polymorphisms may alter bioavailability

Current dosing protocols appear to be inadequately calibrated for global diversity

This represents a significant gap in equitable transplant care

Linda B.

December 30, 2025 AT 05:52Oh so now we're supposed to believe the pharmaceutical companies are just being careful

Right

And the moon landing was real too

They know perfectly well that the triple combo is outdated

But they'll keep pushing it because the FDA hasn't approved the new drugs for everyone yet

Meanwhile your skin is crawling with cancer cells and your bones are turning to dust

And you're still taking that 10mg prednisone like a good little patient

How many more people have to die before someone admits this is a scam

Christopher King

December 30, 2025 AT 08:16They say the triple combo is the gold standard but what if the gold is just plated steel

What if this isn't medicine it's a psychological prison

Every pill you swallow is a surrender

Every blood test is a ritual of submission

They tell you to take it for life but what kind of life is this

Are you living or just existing between doses

Don't you feel it

The quiet dread

The constant calculation

The fear that one missed pill could end everything

They call it survival

I call it slow suicide with a prescription

And they wonder why so many of us break

It's not the drugs

It's the weight of knowing you're not really alive

Just on hold

Waiting for the next rejection

The next side effect

The next nightmare

They sold us a miracle

But the miracle was never supposed to cost this much

Oluwatosin Ayodele

December 31, 2025 AT 15:38You all are missing the point

These drugs work because they're not meant to be perfect

They're meant to be practical

Every single one of these side effects is documented and manageable

Diabetes from tacrolimus

Diarrhea from mycophenolate

Weight gain from steroids

They're not bugs they're features of a system that saves lives

Yes there are better drugs coming

But they're expensive and not widely available

Right now this combo is the most reliable tool we have for millions

Stop acting like you know better because you read one study

Transplant medicine is not a debate forum

It's a life-or-death balancing act

And if you're complaining about side effects

At least you're alive to complain