Antiemetics and Parkinson’s Medications: Avoiding Dangerous Dopamine Interactions

Dec, 29 2025

Dec, 29 2025

For someone living with Parkinson’s disease, nausea isn’t just an inconvenience-it can be a dangerous side effect of the very medication that keeps them moving. Levodopa, the gold-standard treatment, causes nausea in 40 to 80% of patients when they first start taking it. That’s why doctors often reach for antiemetics. But here’s the catch: many of those antiemetics are dopamine blockers. And in Parkinson’s, dopamine is already running dangerously low.

Why Dopamine Blockers Are a Problem

Parkinson’s disease slowly destroys the brain’s dopamine-producing cells. Without enough dopamine, movement becomes stiff, slow, and shaky. Treatment focuses on replacing that lost dopamine-usually with levodopa, often paired with carbidopa to help it reach the brain. Now, think about how antiemetics work. Drugs like metoclopramide, prochlorperazine, and haloperidol stop nausea by blocking dopamine receptors in the brain’s vomiting center. Sounds logical, right? But if those same drugs cross into the basal ganglia-the area already starved of dopamine in Parkinson’s-they make things worse. They don’t just stop vomiting. They can freeze you in place.It’s not theoretical. Patients report sudden worsening of tremors, rigidity, and freezing episodes after being given a simple nausea pill. One man on the Parkinson’s NSW Forum described his tremors exploding after a dental procedure where he was given metoclopramide. It took three weeks to get back to baseline-even after bumping up his levodopa dose.

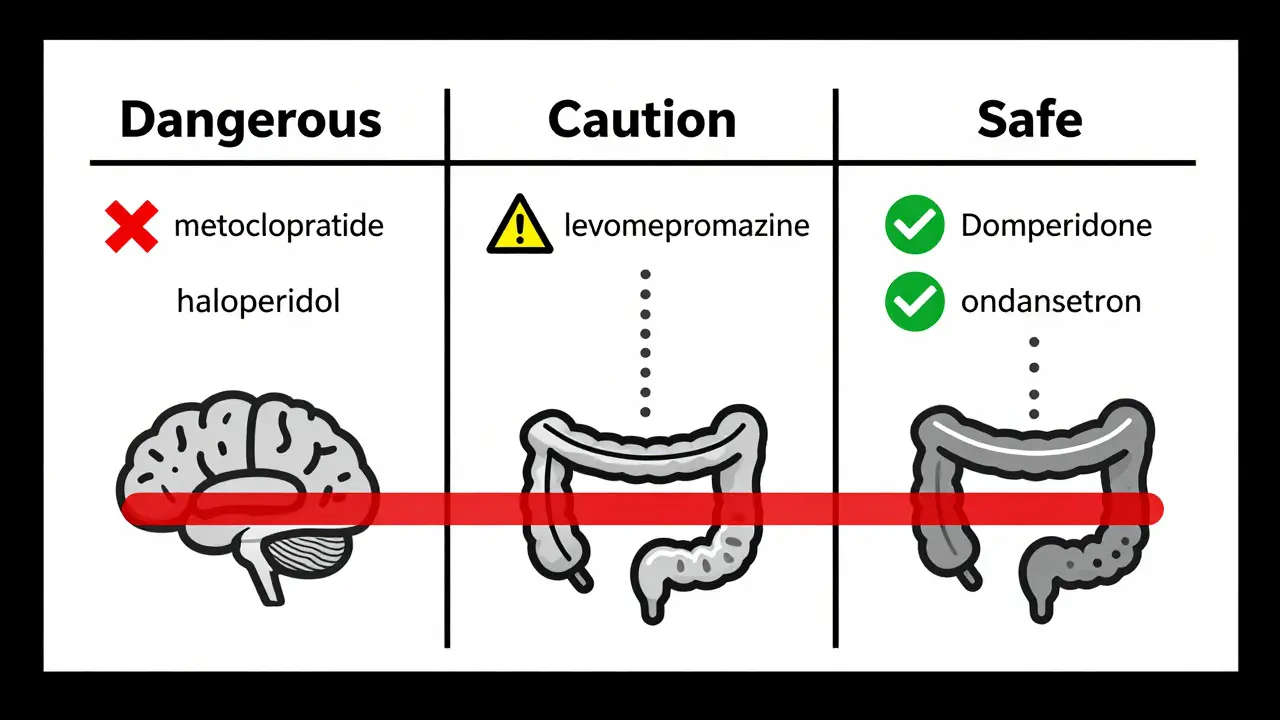

Which Antiemetics Are Dangerous?

Not all antiemetics are created equal. The risk depends on one thing: whether the drug can get into the brain.- High-risk (avoid): Metoclopramide (Reglan, Maxalon), prochlorperazine (Stemetil), haloperidol (Haldol), chlorpromazine, promethazine, droperidol. These cross the blood-brain barrier easily and directly block dopamine receptors where they’re needed most.

- Lower-risk (use with caution): Levomepromazine (Nozamine). It still has some central effect, so it’s only considered after a specialist review and at the lowest possible dose.

- Safer options: Domperidone (Motilium), cyclizine (Vertin), ondansetron (Zofran). These either don’t enter the brain or don’t target dopamine receptors.

The American Parkinson Disease Association’s Medications to Avoid list rates metoclopramide as having a 95% risk of worsening symptoms. Prochlorperazine and haloperidol aren’t far behind. These aren’t just side effects-they’re drug-induced Parkinsonism, and it can take days or weeks to reverse.

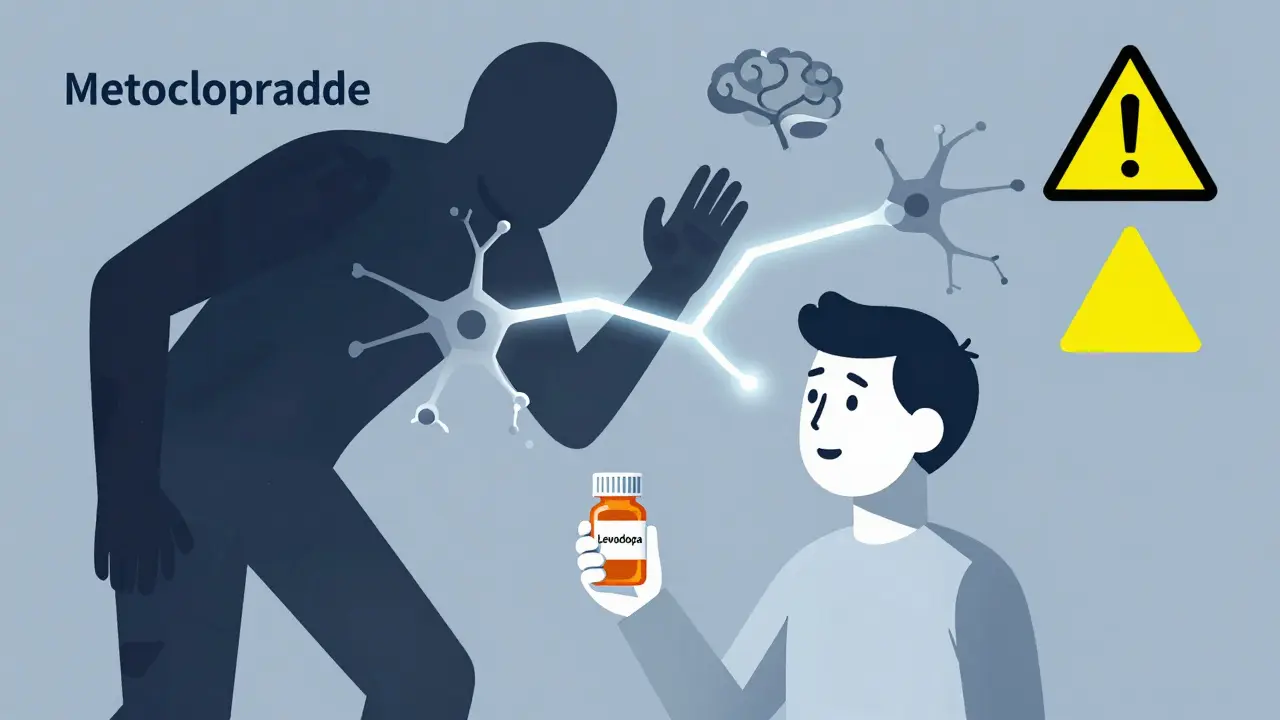

Why Metoclopramide Is Especially Tricky

Metoclopramide is the most commonly misprescribed antiemetic for Parkinson’s patients. It’s cheap, widely available, and used everywhere-from emergency rooms to post-op wards. But here’s the twist: even though it blocks dopamine, some patients don’t get worse. Why?Research from the 1970s, led by Dr. Tarsy, found that metoclopramide also acts as a serotonin 5-HT4 agonist. This might help stimulate gut motility without fully shutting down brain dopamine pathways. But that doesn’t make it safe. Studies show it still causes acute dystonia in 1-10% of users, and in Parkinson’s patients, even small dopamine dips can trigger major motor crashes.

Dr. Alberto Espay from the University of Cincinnati calls it “the single most common medication error” in Parkinson’s care. Emergency doctors don’t know. Pharmacists don’t flag it. Patients don’t speak up. And then they end up hospitalized.

What’s Safer? The Real Alternatives

If you need to treat nausea in Parkinson’s, here’s what actually works without making things worse:- Domperidone (Motilium): This is the gold standard. It blocks dopamine in the gut but can’t cross the blood-brain barrier thanks to P-glycoprotein pumps. Studies show less than 2% risk of worsening motor symptoms. The catch? It’s not available as an injection in the U.S. and requires special access due to FDA restrictions over heart rhythm concerns-though those risks are minimal at standard doses.

- Cyclizine (Vertin): This is an antihistamine, not a dopamine blocker. It has only a 5-10% risk of causing problems. Many patients report dramatic improvements after switching from metoclopramide. One Reddit user said their weekly freezing episodes disappeared overnight.

- Ondansetron (Zofran): Blocks serotonin, not dopamine. Around 15-20% risk, mostly because it’s less effective for certain types of nausea common in Parkinson’s. Still, it’s a solid option when domperidone isn’t available.

- Ginger: A natural option. Taking 1 gram daily in capsule or tea form has shown real benefit in reducing nausea without any drug interactions.

And don’t overlook non-drug fixes: small, frequent meals; staying hydrated; avoiding greasy or spicy foods; and sitting upright after eating. These simple steps can cut nausea by half before you even reach for a pill.

The Real Cost of a Wrong Prescription

This isn’t just about discomfort. Getting the wrong antiemetic can cost lives-and money.A 2022 study found that 68% of Parkinson’s patients who received dopamine-blocking antiemetics in hospitals reported a major spike in motor symptoms. Over 22% needed extended hospital stays. Each incident adds an average of $3,200 in extra care costs.

And it’s happening more than you think. Only 37% of emergency physicians could correctly identify metoclopramide as dangerous for Parkinson’s patients. Meanwhile, 62% of Parkinson’s patients said they’d been given one of these drugs during a hospital visit.

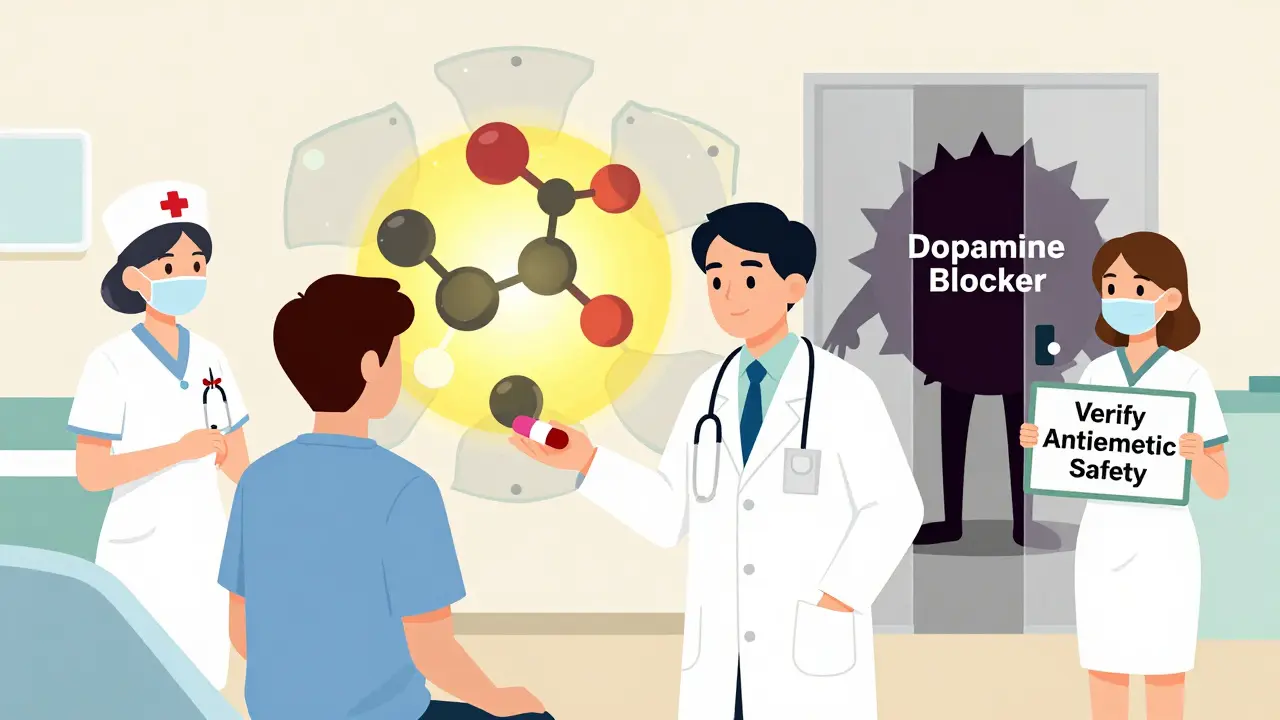

The Movement Disorder Society now requires that every antiemetic order for a Parkinson’s patient include a note: “Parkinson’s disease: verify antiemetic safety.” That’s not bureaucracy-it’s a lifeline.

What Should You Do?

If you or someone you care for has Parkinson’s:- Know the red flags. Avoid metoclopramide, prochlorperazine, haloperidol, promethazine, and chlorpromazine at all costs.

- Carry a list. The APDA’s wallet card (available online) lists safe and unsafe meds. Keep it in your wallet or phone.

- Ask before you take anything. Even over-the-counter motion sickness pills (like dimenhydrinate) can be risky. Always check with your neurologist or pharmacist.

- Push for domperidone or cyclizine. If nausea is persistent, don’t settle for a dangerous fix. Ask for safer alternatives.

- Use ginger. It’s cheap, safe, and surprisingly effective.

There’s hope on the horizon. New drugs like aprepitant (Emend), which blocks a different nausea pathway, are showing 92% effectiveness in trials with zero motor side effects. The Michael J. Fox Foundation is funding research into a new peripheral serotonin modulator designed just for Parkinson’s patients.

But until those arrive, the safest choice is simple: avoid dopamine blockers. Your brain doesn’t need more of them. It needs every bit of dopamine it can keep.

When to Call Your Doctor

If you’ve taken a dopamine-blocking antiemetic and notice any of these within 24-72 hours:- Sudden increase in tremors or shaking

- Stiffness that won’t ease

- Freezing episodes (can’t start walking)

- Slower speech or swallowing

- Increased fatigue or confusion

Stop the medication and call your neurologist immediately. Don’t wait. Don’t assume it’s just a “bad day.” This is a drug reaction-and it’s reversible if caught early.

Shae Chapman

December 31, 2025 AT 00:37OMG I just read this and cried 😭 My mom got prescribed metoclopramide after her gallbladder surgery and she froze for 3 days-couldn’t walk, couldn’t talk. We thought it was her PD worsening… turns out it was the drug. I’m screaming at every doctor I meet now. Please, please, please share this. 🙏

Nadia Spira

January 1, 2026 AT 22:19Let’s be clear-this isn’t medical advice, it’s a pharmacological tragedy engineered by corporate indifference and neurologists who don’t read journals. The FDA’s regulatory capture is why domperidone is banned while metoclopramide floods ERs. This is neoliberal healthcare in action: profit over proprioception. The 95% risk metric isn’t even statistically robust-it’s a moral indictment.

henry mateo

January 2, 2026 AT 17:08just wanted to say thank you for writing this. i had no idea domperidone was even a thing. my dad got stuck on promethazine for months and i never connected the dots. i’m printing this out and taking it to his neurologist next week. also… sorry for the typos, typing on my phone and my thumbs are tired 😅

Kelly Gerrard

January 2, 2026 AT 21:39This is a critical public health issue that demands immediate systemic reform. The failure of emergency protocols to integrate Parkinson’s-specific pharmacology is indefensible. Domperidone must be made universally accessible. Ginger is not a substitute-it is a supplement. We must advocate for policy change, not just patient awareness.

Glendon Cone

January 3, 2026 AT 07:53Big thanks for laying this out so clearly. I’m a pharmacist and I had no idea how common this mistake was. I just added a pop-up alert in our system for Parkinson’s patients trying to fill metoclopramide. Also, ginger tea is my new best friend-my aunt swears by it. 🌿☕️

Henry Ward

January 3, 2026 AT 16:30So let me get this straight-you’re blaming doctors for following guidelines while ignoring the fact that most patients don’t even know they have Parkinson’s until it’s stage 3? You’re acting like this is a conspiracy. It’s not. It’s bad communication. Stop pretending you’re the only one who cares. Also, domperidone causes QT prolongation. You’re just swapping one risk for another. Thanks for the fearmongering.

Joseph Corry

January 4, 2026 AT 13:42Interesting. But you’ve conflated pharmacokinetics with phenomenological experience. The dopamine hypothesis is itself a reductionist relic of mid-20th century neurochemistry. We must deconstruct the binary of ‘safe’ and ‘dangerous’-what if the ‘worsening’ is merely the unmasking of latent nigrostriatal pathology? The real issue is epistemic arrogance in clinical decision-making.

Cheyenne Sims

January 6, 2026 AT 11:58As an American, I find it unacceptable that a life-saving medication like domperidone is blocked by bureaucratic red tape while dangerous alternatives are freely prescribed. This is not just a medical failure-it’s a national disgrace. We need legislation. Now.